Inquiring about students’ gender pronoun preferences may, at first, feel awkward for leaders in the classroom. This discomfort may be a result of feelings of uncertainty about how to ask students about their gender identity. Uneasiness may also stem from uncertainty about how to maintain an atmosphere of mutual respect over the course of a semester.

Professors must decide individually whether (and how) to collect this information. There are at least two considerations that may influence this decision:

Instructors’ views on these questions likely shape their beliefs about the most appropriate course of action.

There are a variety of approaches that can be adapted by instructors based on the discipline, class size, course topic, etc. These approaches include:

Once you have collected students’ requested names, it is important to honor these requests in all course-related classroom interactions. Doing so fosters a sense of mutual respect that is crucial in cultivating inclusive classrooms.

| Here are several techniques for learning (and remembering) students’ names |

Finally, when gathering information about students’ gender identity, it is imperative that course instructors not expect gender non-conforming students to “represent” the “gender non-conforming perspective” in classroom discussions. Instead, consider including course materials that offer feedback from self-identified gender non-conforming scholars to flush out the multitude of perspectives on a given topic (Abbott 2009). The latter approach reduces the burden placed on gender non-confirming students.

Source: Teaching Beyond the Gender Binary in the University Classroom

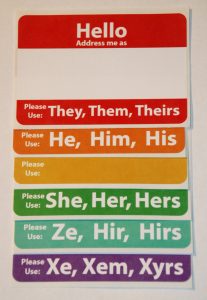

1. Ask students their preferred name and the pronouns they use at the start of the semester (and respect them). Tell your students your preferred name and the pronouns you use at the start of your first class.

The beginning of the school year can be stressful for transgender and non-binary students, especially if they are taking classes with professors whom they do not already know. Legal barriers often prevent students who use a different name from the one they were assigned at birth from changing it to reflect their gender identities. Consider pedagogical practices that allow students to self-identify instead of relying on the roster you receive at the beginning of the school year.

Tips

2. Highlight the UA non-discrimination policy when going over the syllabus.

This benefits ALL students by emphasizing UA’s and your commitment to diversity and inclusion. This statement includes both sexual orientation and gender identity.

3. Familiarize yourself with the restrooms on your classroom’s floor and highlight the location of the nearest gender neutral bathroom on the first day of class.

Restroom access can be a stressful for transgender and non-binary students on campus. Identifying the nearest inclusive

bathrooms alleviates the need for students to research building floor plans for each class they take each semester. Directing students to the nearest gender neutral bathroom assists all students in the class.

NOTE: UA has a restroom access policy that affirms that an individual’s use of the restroom that corresponds to their gender identity.

4. Use inclusive language in your class.

Avoid using words like "ladies and gentlemen" or "boys and girls" when referring to your class. Use more inclusive language like "folks" "everybody" or "people".

5. Weave LGBTQ content and materials throughout course curriculum.

Providing students with a course outline that includes LGBTQA+ content is one means of explicitly challenging heterosexist

assumptions and misconceptions. Whenever possible, disperse LGBTQA+ readings and discussion throughout a course to avoid creating the impression that LGBTQA+ course content can only be tangential to the goals and activities of your discipline.

NOTE: Emily Style (1996) suggested that curriculum should provide both “windows and mirrors”. “Windows” allow all students to “understand the [multiple] experiences and perspectives of those who possess different identities”. Additionally, mirrors benefit LGBTQA+ students by “reflecting individuals and their experiences back to themselves”.

6. Challenge heterosexist assumptions.

Throughout their lives, many LGBTQA+ students have been given the implicit message that heterosexuality is the norm. In the classroom, the presumption of heterosexuality places an unfair burden on LGBTQA+ students to silently suffer feelings of exclusion or to “out” themselves. Faculty can reduce that burden by taking a personal inventory of heterosexist assumptions followed by specific actions to demonstrate that we recognize, respect, and value students of diverse sexual and gender identity in the classroom.

7. Develop inclusive rather than “us”/”them” terminology.

Develop a pedagogical style that avoids using language that implies heterosexist classroom norms. For example, the use of “we” in the following well-intentioned sentence may nonetheless support assumptions of LGBTQA+ classroom minority status: “Even though it is outside our experience, we need to try and understand the life challenges of persons who are LGBTQA+.” An alternative might be “All students benefit from understanding the life challenges of persons who are LGBTQA+.”

8. Increase visibility of LGBTQ role models and allies.

Visible LGBTQA+ adult role models are often absent on campus. Whether or not one identifies as LGBTQA+, all faculty can be visible as LGBTQA+ allies through participation in or leadership in creating University sponsored LGBTQA+ activities that demonstrate how we live out the University of Arizona’s mission with regard to respect and caring for LGBTQA+ students. When LGBTQA+ topics are less salient to specific course content, faculty can select readings authored by, or bring in speakers, who are openly LGBTQA+ and experts in the course content area.

9. Create a classroom climate in which the perspectives of LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ students are valued.

Nurturing respectful dialogue on LGBTQA+ relevant issues requires faculty sensitivity to the ways in which all students struggle on their path toward development as a whole person. Moving the student body in the direction of LGBTQA+ inclusiveness requires both the continued affirmation of LGBTQA+ human rights and dignity as well as sensitivity to heterosexual students who may be struggling with societal and personal biases and misconceptions.Comments in the classroom that stigmatize or hurt LGBTQA+ students should always be addressed since silence may be seen as confirmation of such beliefs. Addressing such comments without condemning the student(s) who made them provides faculty the opportunity to foster classroom dialogue that respectfully reflects commitments to life-long learning.

10. Master the art of “bumbling.”

All teachers have experienced times when to our deep consternation we realize we have used a poorly chosen phrase that may have created discomfort or unintentionally exacerbated feelings of exclusion. Rather than avoiding LGBTQA+ topics for fear of saying the wrong thing, faculty can embrace our vulnerability to misstatements and commit to attaining the knowledge necessary to address student misconceptions or discomforts in the next class session. This technique also provides a model for students of openness to others and the value of life-long learning.

11. Include your pronouns in your email signature and syllabus.

Ex. J. Smith

Assistant Professor of Sociology

Pronouns: She/Her/Hers

University of Arizona

Ph: (520) 555-5555

12. Complete Safe Zone training.

The University of Arizona’s Safe Zone program provides the campus with basic LGBTQA+ cultural competency. After completing both General Education and Ally Development workshops, participants are given a placard to place on their office doors. A 2011 review of the program determined that 90.1% of respondents feel better about the campus climate towards LGBTQA+ people when they saw safe zone placards. Additionally, 73.6% felt safer in areas where Safe Zone placards were displayed, regardless of their sexuality or gender identity.

Visit the Safe Zone Website for more information.

Conflict may arise when creating (and trying to maintain) a gender-inclusive classroom environment. In these moments, instructors and teaching assistants may feel uncertain about how to appropriately intervene, particularly when a student has been misgendered or when other microaggressions occur. Despite discomfort, it is the instructor and teaching assistants’ role as the leaders in the classroom to intervene. This is often the case even when these “teaching moments” are not directly related to the course content.

One of the best ways to maintain a positive classroom environment is be proactive about establishing norms of mutual respect from the first class meeting. For many instructors, it is customary to communicate expectations about course assignments and attendance on the first day; however, incorporating expectations about healthy communication, conflict and respecting one another’s gender identity tends to be more rare. As a result, instructors may miss an important opportunity to cultivate a welcoming and gender-inclusive classroom atmosphere.

For those who choose to communicate their expectations about communication, conflict and mutual respect, there are many ways this conversation might unfold. One possible approach is to begin the semester with a conversation about the importance of honoring one another by correctly pronouncing names and using requested pronouns.

Another approach is to develop a document that outlines your expectations of mutual respect and present it to students during the first week of class. After presenting it to students, you might allow them to add to the document and use the final product as “ground rules” in your classroom.

This mutual respect document was developed in the Physics department at Ohio State University.

Beginning the course in this way provides an opening to talk about conflict before it arises. As part of this conversation, you might discuss how you will react when a student or you yourself misgenders a student. Some phrases might include:

Discussing this language outside of a “hot moment” allows students to learn about issues of gender identity and expression without activating defensive reactions. Moreover, it may head off potential conflict by having students engage in these important conversations before a breakdown of understanding occurs.

When hot moments do arise, it is not advisable to avoid difficult or uncomfortable conversations. While it may feel awkward to stop and correct your (or a students’) pronoun usage, failing to act is a personal affront (and a violent act) against gender non-conforming individuals.

Remember, students will naturally look to you for cues about the importance of gender-inclusivity owing to your role as a leader in the classroom. Be mindful of the verbal (and non-verbal) messages you send. If you are consistent in using students’ requested names and pronouns, in most cases students will follow your lead and exert a similar level of effort in respecting their peers’ gender identity and expression.

Source: Teaching Beyond the Gender Binary in the University Classroom

Main Library | 1510 E. University Blvd.

Tucson, AZ 85721

(520) 621-6442

University Information Security and Privacy

© 2023 The Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of The University of Arizona.