Even if you do not specialize in LGBTQIA+ healthcare, it is important for all medical providers to have some background in issues facing this community. In 2010, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion released the “Healthy People 2020” initiative, a 10-year agenda for improving the nation’s health. One segment of this project researched and identified unique health improvement priorities for the LGBTQIA+ community.

Try It!Before reading on, take a moment to think about what you know about healthcare disparities faced by the LGBTQIA+ community. What are some of the reasons these disparities might exist? |

It is important to note that historically many of the healthcare disparities faced by the LGBTQIA+ community – such as experiencing higher rates of HIV and other STIs – have been attributed to the “lifestyle habits” of individuals, leading to increased stigmatization and pathologization of sexual and gender minorities (Ard and Makadon, 2012). As a provider, when addressing healthcare disparities, it is crucial that you recognize that the challenges faced by LGBTQIA+ folks are not their personal fault but instead are symptom of larger social inequalities (legal, medical, cultural, etc.) and that you reflect this understanding in your language. For example, in relationship to sexually transmitted infections, LGBTQIA+ individuals are far less likely to receive relevant safer sex education, to have access to screening services, and to have access to consistent sexual healthcare. Relatedly, healthcare disparities may be compounded based on other social identities that LGBTQIA+ patients have, such as their race/ethnicity, income, geographic location, educational level, immigration status, and language (The Joint Commission, 2011).

A 2011 report released by the Institute of Medicine suggests contextualizing healthcare disparities experienced by the LGBTQIA+ communities via four conceptual perspectives:

According to Healthy People 2020, some of the primary health-related disparities experienced by LGBTQIA+ communities are:

First impressions leave lasting impressions. When thinking about healthcare, some consider interactions between provider and patient to be the first moment at which rapport is established. In actuality, for many LGBTQIA+ patients, the communication of whether a medical center will be inclusive begins the moment that we walk through the door.

There are many ways in which inclusivity can be indicated before the patient meets with their provider:

Space Decor and Materials

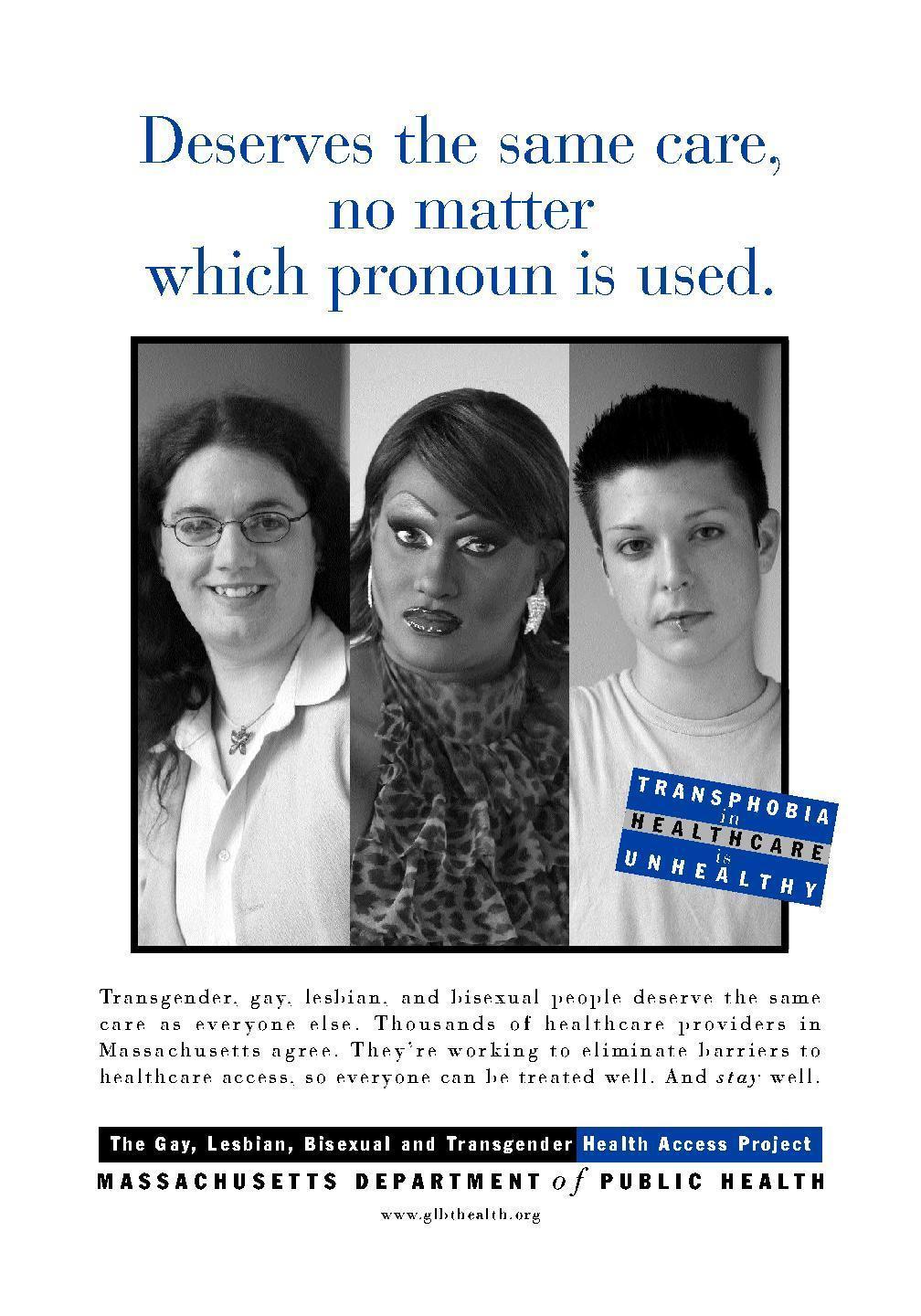

One easy way to indicate that a space is LGBTQIA+ inclusive is to make representations of these identities readily visible. LGBTQIA+ folks are often attuned to keep an eye out for subtle markers of acceptance, such as SafeZone stickers, rainbow or transgender pride flags, or posters that include images of queer people (of various races, ethnicities, disabilities statuses, religions, etc). Folks might also be on the lookout for pamphlets and educational materials that address the needs of the LGBTQIA+ community (Wilkerson et al, 2009). In addition to indicating inclusivity, these resources might provide patients with some of the healthcare information that they are looking for.

Nondiscrimination Policy and Patient Bill of Health

The Joint Commission also suggests prominently displaying the medical center’s nondiscrimination policy or patients’ bill of rights, making sure that both of these documents clearly state an individual’s right to equitable healthcare regardless of their sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and sex assigned at birth (Joint Commission, 2011).

Of course, visual indicators in the waiting area cannot alone create an LGBTQIA+ inclusive environment. Instead, these markers must be coupled with action – providers taking intentional steps to practice inclusiveness in all patient interactions.

Try It!What are some ways in which your waiting area is explicitly inclusive of LGBTQIA+ patients? What are some ways you would like to change your waiting area to improve inclusivity? |

It is important to make sure that all patients, even in waiting areas, have access to accessible, all-gender or single-user restroom facilities. Sometimes these types of facilities are referred to as “unisex” or “family restrooms.” While these facilities are functionally the same, clearly designating a restroom as “all-gender” is a powerful signal of inclusivity for LGBTQIA+ folks. Here are two sets of commonly-used signage (based on the restroom’s degree of accessibility). The symbol of the toilet is preferred to that of the “half woman/half man,” which is perceived as being pejorative by some transgender people.

If all-gender restrooms are offered alongside gender-specific facilities (i.e. women’s room and men’s room), LGBTQIA+ individuals should be allowed to use the restroom of their choice. In other words, LGBTQIA+ should never be forced to use an all-gender restroom in lieu of a gender-specific restroom if they would prefer the latter. It could be helpful to include a restroom access statement under all bathroom signs indicating that individuals can use the restroom that best aligns with their gender identity regardless of assigned or legal sex.

All restrooms, regardless of gender specification, should be equipped with disposal units for sanitary products. While this is common practice in women’s restrooms and all-gender restrooms, men’s restrooms often lack these units. It is important to ensure that there are discrete means for disposing of sanitary products in men’s rooms just in case a trans man or other person who is menstruating uses this facility.

Try It!Think about the location of the nearest all-gender or single-restroom facility to your office. Is it ADA-accessible? Is it convenient for patients? If not, what are some ways you can improve these levels of access? |

Intake forms are important ways of gathering information. Unfortunately, many intake forms fail to be inclusive of LGBTQIA+ identities. This issue both contributes to and is compounded by the hesitance that a patient might have to share personal information with their healthcare provider. Having more inclusive questions and response options on intake forms can positively contribute to higher levels of patient trust and comfort. It also makes it more likely that healthcare providers are receiving accurate information about their patients that is relevant to their healthcare.

General Information

• Disclaimer: Many LGBTQIA+ patients might be hesitant in sharing some of the information included in intake forms out of fear that they will be discriminated against based on their identity. It is therefore useful to include a disclaimer somewhere at the beginning of your intake form. Take, for example, this note that Lyon-Martin Health Services utilizes: “We will NEVER penalize you or deny you care based on what you tell us on this form. If you feel uncomfortable answering a question, leave it blank.”

• Name: Some transgender individual’s names might not match the name that is on their legal documents (i.e. birth certificate, driver’s license, insurance card). Intake forms should include a space both for the name that is on one’s insurance card (for legal purposes) and the name that someone uses for themselves (to respect and refer to the patient properly). It is important that everyone— from the front desk to the examination room – uses an individual’s preferred name, not the name on their insurance (i.e. when calling for a patient in the waiting room, staff should use the patient’s preferred name or simply their last name to avoid accidentally misgendering someone). While it is important to ask patients about their preferred name, it is even more important to be sure to use that name even during the hustle and bustle of the

workday.

• Pronouns: In addition to a person’s name, it is important to refer to them using the gender pronouns that they have designated for themselves. Rather than assuming what pronouns a patient might use based on their appearance, a patient should be given space to write in their pronouns on their intake form so that staff refer to them appropriately.

• Sex Assigned at Birth/Gender Identity: Asking transgender and intersex individuals about the anatomy that they have can often be tricky. For example, a trans men who has not had gender affirming surgery or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is likely to still record his sex/gender as male on an intake form. This may lead a practitioner to be confused about what kind of anatomy a patient has, information that might be relevant to their care (i.e. a trans man might have a cervix therefore should be informed of related cancer-screening processes). For medical purposes, you may need to know what sex a person was assigned at birth in order to better provide care related to different anatomical parts. While you can ask someone what their sex assigned at birth is, you should also always make space for a person to declare

their gender identity. A person might elect to leave this space blank, and this should be respected; however for many

transgender people, asking about gender identity on an intake form is affirming.

“I’d rather live in a world where, I go to my doctor’s office and not feel like I have to keep information about my life secret in order to have a safe and respectful healthcare experience. But we don’t like in that world.” - a transgender patient (Wilkerson et al, 2009).

Because of experiences with discrimination both inside and outside of the medical context, some LGBTQIA+ patients may be uncomfortable at the doctor’s office, and it could take some time to earn their trust. Understanding some of the reasons why LGBTQIA+ may be hesitant to go to the doctor is an important step to repairing these fissures. Here are some of the main concerns that many LGBTQIA+ individuals have in going to the doctor:

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, and other non-heterosexual patients:

Many LGBQ+ patients feel very anxious about sharing their sexual orientation out of fear that a practitioner might be homophobic. They fear

that their provider will seem uncomfortable or judgmental if they disclose information about their sexuality. Many patients even (rightfully) worry that they will receive substandard care if they are open about their sexual orientation. For example, in some states, Religious Freedom Restoration Acts may allow healthcare providers to legally justify refusing to treat a patient because they are LGBTQIA+ (i.e. Michigan’s HB 5958). LGBQ+ individuals are often stigmatized as having “loose sexual morals.” This is particularly true of those who have been romantically and/or sexually involved with partners of multiple genders and of those who are polyamorous. Some LGBQ+ individuals do not feel the need to share information about their sexuality with their healthcare provider; however others would like to be able to, particularly as relates to their sexual health.

Transgender patients:

More so than LGBQ+ patients, transgender patients are very uncomfortable in the medical context (Ard and Makadon, 2012). In addition to fearing discrimination and transphobia, many transgender patients have also felt exploited by medical practitioners. For example, transgender patients are often at the will of healthcare providers when it comes to being able to have surgical procedures and hormonal treatments to medically transition. Having to receive a diagnosis of “gender dysphoria” is experienced negatively by many transgender individuals, who feel as though their identity is being treated as a disease or disorder to be fixed (this is referred to as pathologization or medicalization). Additionally, many transgender patients experience heightened dysphoria in medical settings because of the intimate focus on their bodies (and, although this can be avoided, by the gendering of their anatomy in these settings).

Intersex patients:

Many intersex individuals also feel as though their bodies are being pathologized or labeled as “abnormal.” This has remained true after the release of the “Consensus Statement on the Management of Intersex Disorders” in 2006, which changed the nomenclature of intersex conditions to “disorders of sexual development” (Lee et al, 2006). Whereas many transgender individuals are uncomfortable in the medical context because of a lack of access to care, many intersex individuals experience discomfort or even post-traumatic stress when visiting doctors because of the physical examinations and procedures that they may have been non-consensually subjected to during infancy and childhood. Many intersex patients undergo “corrective surgeries” on their genitalia and gonads while they are still too young to provide consent. Instead, these procedures are performed based on parental consent alone, which many intersex patients experience as disempowering and violating. Historically, some intersex children were not informed of the real reason why these procedures were being performed (i.e. they were told they had a hernia repair to cover up that they had gonads removed), leading to increased distrust towards healthcare providers (Karkazis, 2008). This also means that many intersex patients might not have been provided with full access to their medical histories even as adults.

With this knowledge in mind, here are some steps that healthcare providers can take to build trust between themselves and LGBTQIA+ patients during their interactions:

Do not assume: Regardless of a patient’s appearance, do not assume that you know their gender identity, pronouns, sexual orientation, or what anatomy they might have. Intake forms are a good place to learn some of this information. Always be sure to carefully review a patients information – especially their name and pronouns – before greeting them. Recognize this information may change over time. Avoid greeting people as “sir” or “ma’am” unless you have confirmed their gender identity.

Do not pressure patients to disclose: Some patients may be uncomfortable sharing that they are LGBTQIA+. This may be particularly true of patients who are accompanied by a parent, guardian, assistant, or caretaker (with whom they may not have disclosed their LGBTQIA+ identity). A person should never be pressured by a medical practitioner to reveal their gender identity or sexual orientation. Instead, a practitioner should work on creating an open and inclusive space that will make the patient more comfortable disclosing should they decide to do so.

Be conscious of language when discussing the body: In addition to respecting patients’ names and pronouns, healthcare providers should be careful about the language that they are using. In medicine and the natural sciences, there is usually an underlying assumption that there are two “biological sexes” – female and male – and that certain traits and body parts fall into either of those groups. This is very exclusionary of transgender and intersex patients. Some of these individuals might identify as female or male but will have anatomies that are different than what you might expect. For example, a woman who identifies as female may have Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome (AIS) and might not have a uterus. In another case, a transgender man who identifies as male might have a vagina and ovaries, not a penis and testes. Further, some patients may not identify as either female or male, such as non-binary individuals. To be inclusive of transgender and intersex patients, avoid gendering different body parts (e.g. describing certain anatomy as “female” and other anatomy as “male”). For example, let’s say that you want to encourage your patient to have a PAP smear. Instead of saying “Women should have regular PAP smears to screen for cervical abnormalities,” you could instead say, “People who have cervixes should have regular PAP smears to screen for abnormalities. Have you had a PAP smear? Should we schedule one?” By not “gendering” certain body part and instead discussing the parts themselves (i.e. people who have penises; people who have testes; people who have vulvas), your language is much more inclusive and less likely to cause dysphoria and discomfort.

Avoid treating bodies as disorders: This can be difficult to do because of the existing medical script; however it is important to try to avoid language that can be pathologizing to patients. For example, instead of referring to being intersex as having a “disorder of sexual development,” you can use the phrase “difference of sexual development” (as is recommended by both the Accord Alliance and OII Intersex Network). If you have to use a label such as “gender dysphoria” for the purposes of insurance, be sensitive to the feelings that a transgender patient might have about this diagnosis. For example, you can explain to a patient that using the language of “gender dysphoria” is necessary because of the code that insurance companies need to approve treatment. At the same time, you can express sympathy by affirming that there is nothing “wrong” or “disordered” about being transgender, and that your goal is to make sure that the patient is able to receive the gender affirming care that they need.

Main Library | 1510 E. University Blvd.

Tucson, AZ 85721

(520) 621-6442

University Information Security and Privacy

© 2023 The Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of The University of Arizona.