The first step to providing more LGBTQIA+ inclusive healthcare is having a better understanding of gender and sexuality more broadly. The “Gender Unicorn,” produced by Trans Student Equality Resources (TSER), is an excellent tool to begin understanding different aspects of these identities. When we think about identity, we often think in terms of either/or. For example, we think a person is a woman or a man, feminine or masculine, gay or straight. In actuality, identity is much more complicated than these binary relationships suggest and is more accurately understood as a series of interrelated continua. Using the graphic below, we can imagine that people’s identities existed somewhere on or outside the different “scales.” Some peoples’ identities remain static and unmoving, while others might change (but aren’t any less valid).

Gender Identity: Gender identity is one’s internal sense of being a woman, man, both, neither, or something else entirely. On the Gender Unicorn, gender identity is represented by the thought bubble. Because it is an internal sense of self, you cannot know someone’s gender identity just by looking at them.

Gender Expression/Presentation: Gender expression is how a person physically presents themselves as feminine, masculine, androgynous, or some combination thereof. This might involve the way a person dresses, how they style their hair, or their body language. Gender expression is not the same thing as gender identity. For example, someone might identify as a man and express themselves through a feminine appearance. In other words, to be feminine is not always synonymous with womanhood, even though we are often socialized to believe so in the United States. What is understood as feminine or masculine can also vary based on cultural and social context.

Sex Assigned at Birth: Sex assigned at birth (represented by the DNA on the Gender Unicorn) is the category of female, male, and/or intersex that a person is assigned by medical professionals after they are born based on their chromosomes, anatomy, and hormones. Sometimes, this is referred to as “biological sex”; however there has been a movement away from this language because it implies that a person’s assigned sex is more legitimate than the sex they identify with. This belief can be particularly marginalizing to transgender and intersex communities.

Sexually Attracted To: Sexual attraction is the types of identities, expressions, and sexes that a person is sexually oriented towards. Some people do not experience sexual attraction, or they only experience it under certain circumstances. These folks may call themselves asexual or gray-sexual.

Romantically/Emotionally Attracted To: Emotional attraction is the types of identities, expressions, and sexes that a person is romantically oriented towards. Some people do not experience romantic attraction, or they only experience it under certain circumstances. These folks may call themselves aromantic or gray-romantic.

Try It!Take a moment to fill out the Gender Unicorn for yourself. Reflect on your own positionality, as well as other social identities that you hold (e.g. race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, disability). How do these identities impact your work as a healthcare provider? More specifically, how might these identities impact the interactions that you have with patients? |

Never “out” someone: LGBTQIA+ individuals — especially transgender and gender non-conforming communities of color — experience some of the higher rates of violence worldwide. In the United States alone, 2016 was the considered the “deadliest” year for transgender Americans, with 27 reported murders (Ring, 2017). This does not take into account the number of unreported murders or reported murders in which the individual was misgendered. LGBTQIA+ individuals also experience employment discrimination, medical discrimination, and harassment in some contexts when they disclose their sexual and gender identity. If someone discloses their LGBTQIA+ identity to you and you are unsure of how “out” they are, a safe bet is asking them privately.

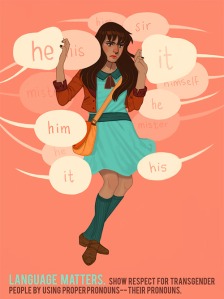

Practice gender inclusive language: Things like including your pronouns in your email signature or introducing yourself with your pronouns can create help create an LGBTQIA+ inclusive environment. Practicing gender inclusive language in general also produces a more affirming environment and helps you to avoid making assumptions about the gender identity that a certain person or their loved ones have.

Note: Under certain circumstances, an LGBTQIA+ individual may not be “out” about their identity. This makes careful attention to the use of language (i.e. names and pronouns) even more important. If you are unsure of whether or not to use certain language to describe someone in a given context, privately discuss this with the person in advance. This might be particularly important to discuss with patients who have caregivers that they may not have disclosed their LGBTQIA+ identity to, such as youth and elderly patients. For more information on language, see pages 13-15.

Do not ask invasive questions: You would be surprised how often people feel comfortable asking LGBTQIA+ folks very personal questions. Oftentimes, we are asked about what body parts that we have, if we are planning on having surgery or what surgical procedures that we have had done, how we have sex, who we have had sex with, what our “real” name is... the list is endless. As a medical provider, some of this information may be pertinent to the care that you are providing. Generally speaking, before you ask an LGBTQIA+ person an invasive question such as the above, ask yourself why you are asking the question. Is it because it is professionally necessary or to satisfy your own curiosity? If the latter is the case, abstain from asking (Ard and Makadon, 2012). If the information is medically relevant, Part III of this guide provides some tips on how to ask these sorts of questions in a way that mitigates discomfort and harm.

Recognize that no two LGBTQIA+ people have the same experience: This is especially true when considering intersectional identities. QTPOC (queer/trans people of color), disabled folks, undocumented folks, poor folks, women and femmes, and other LGBTQIA+ people with multiple experiences of marginalization often have distinct sets of needs. LGBTQIA+ people also have unique experiences with healthcare. Transgender and intersex communities are more likely than LGB individuals to feel uncomfortable with and/or to avoid seeking medical care (The Fenway Institute, 2013). Transgender individuals often experience discrimination and misgendering in healthcare contexts, and they are more likely that LGB individuals to not have healthcare insurance. Intersex individuals often have had deeply traumatizing experiences in the medical context, such as non-consensual examinations and procedures and therefore might be reticent to see a healthcare provider.

Call out homophobic and transphobic behavior: If you witness someone being harassed or discriminated against because of their LGBTQIA+ identity, intervene. This is especially true if you are cisgender and heterosexual, because in these instances you have the benefit of being able to address homophobia and transphobia without as much risk.

Educate yourself: Continue to learn about LGBTQIA+ identities and experiences. Keep up on issues related to LGBTQIA+ justice – both inside and outside of the healthcare context – and engage in related activism. For more information and ways to get involved, visit: https://www.transequality.org/

Note: as its creator is a native English speaker who has lived primarily in the United States, this module’s discussion of language may fail to capture the needs of non-English-speaking or non-native English speaking communities as well as communities living in or coming from different national contexts. Language-use also sometimes varies based on an individual’s membership of a specific racial or ethnic group.

When interacting with LGBTQIA+ individuals in any capacity, the language that we use takes on particular importance.

Although it might seem less apparent than in “romance languages” like French (in which nouns are explicitly “feminine” or “masculine”), the English language and its practices are also extremely gendered. Oftentimes, without even realizing it, we feminize and masculinize language based on certain unconscious assumptions that we have. For example:

Changing our language to be more inclusive involves making some of our language gender neutral, particularly if we do not know the gender identity of all of the people that we are addressing or referring too (again, avoid making assumptions about people’s identity based on their appearance!).

Using gender inclusive language takes conscious effort when you are not used to it, so do not be afraid to practice. Take the time to correct yourself if you notice yourself using language that is not inclusive. This helps reinforce the habits that you are trying to build.

Try It!The following are several phrases that can be made more gender inclusive. How would you correct these sentences? Example 1) "Welcome ladies and gentlemen! Thank you for coming." Example 2) "Please have patient fill out his/her name." Example 3) "For the holiday party, please feel free to bring your husband or wife."

Possible Responses: Example 1) "Welcome everyone! Thank you for coming." Example 2) "Please have the patient fill out their name." Example 3) "For the holiday party, please feel free to bring a guest!" |

|

Another major aspect of gender-inclusive language is using someone’s pronouns. In other words, this means that when you refer to a person, you use pronouns that are reflective of their gender identity and that they want others to use to reference them. Just as you cannot assume someone’s gender identity, you cannot assume the pronouns that someone would like to be referred to by based on their appearance.

Sometimes, in conversations about transgender identity, pronouns are referred to as “preferred gender pronouns” (PGPs); however there has been movement away from this language because the word “preferred” implies that someone could elect to use pronouns other than the ones a person has chosen for themselves. This, however, is not the case.

Some people are uncomfortable using pronouns that they are not familiar with (i.e. gender neutral pronouns such as they/them/theirs (to refer a singular person) or xe/hir/hirs). In other instances, people who have gotten used to using one set of pronouns in reference to a person might be resistant to changing their language if that person transitions to using a different set of pronouns. Not respecting a person’s pronouns for any reason is not okay, and using someone’s pronouns is a vital part of respecting their identity. Very often, for transgender individuals, choosing one’s pronouns is an important part of the coming out process and of being open about their gender identity. It can also be a matter of physical and emotional safety.

The only time it would be appropriate to not use the pronouns that a person identifies with is during situations where this person has told you that they are not out. For example, if you have a friend who is a trans man and uses he/him pronouns socially but who is not "out at work, this person might request that you use a different name and set of pronouns to refer to him if you are ever visiting his office or talking to one of his coworkers. If you are unsure of how to refer to someone in a given space or with certain people, it is always a good idea to respectfully ask them in private.

Here is a chart of some commonly used pronouns:

Pronoun Chart(this list is not exhaustive) |

|||

| Subjective | Objective | Possessive | Example |

|

She |

Her |

Hers |

She is here. I see her. That book is hers. |

|

He |

Him |

His |

He is here. I see him. That book is his. |

|

They (singular) |

Them (singular) |

Theirs (singular) |

They are here. I see them. That book is theirs. |

|

Xe |

Hir (pronounced "here) |

Hirs (pronounced "heres" |

Xe is here. I see hir. That books is hirs. |

Misgendering is using pronouns or other gendered language to refer to someone in a way that doesn’t reflect their gender identity. For example, someone might misgender a trans woman by calling her a boy or referring to her as “he.” Another example would be a woman referring to a group of people that she thinks is all women as “ladies” without realizing that there is a non-binary person in the group. Misgendering is experienced as invalidating and alienating. Misgendering can also contribute to gender dysphoria, which is anxiety, discomfort, and/or depression that a transgender person might experience based on association with their sex assigned at birth. Sometimes, it can be difficult to adjust to using someone’s pronouns, especially if you are accustomed to referring to them in a different way. Here are some tips, some of which are derived from the work of the University of Wisconsin: Milwaukee’s LGBT Resource Center (https://uwm.edu/lgbtrc/

Try It!To practice using different gender pronouns, check out this website: https://www.practicewithpronouns.com/ |

Main Library | 1510 E. University Blvd.

Tucson, AZ 85721

(520) 621-6442

University Information Security and Privacy

© 2023 The Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of The University of Arizona.